Identifying your ICP is an essential component of nailing down your pricing strategy. What price are your customers likely to accept? Is your use case going to be essential enough that it justifies the price for them?

It's a tricky balancing act. To get to the bottom of this, we sat down with three experts from Smallpdf.

In this article, they took us through their journey over the last year and how that's enabled them to understand their customers, build a product for them, market to them, and align their pricing strategy to reflect the value that they get from the product.

But first, here's a breakdown of our main talking points:

- Our roles at Smallpdf

- Smallpdf’s humble beginnings

- Identifying the most valuable customers

- Quantitative and qualitative profiling

- Understanding the opportunities and adjusting the strategy

- Aligning acquisition and product

- Identify pricing that aligns with customer value

- Testing the new pricing and rolling it out

Our roles at Smallpdf

Dominik Hiller: Hello, I’m Dominik, I’ve been working in Strategy and BizDev for Smallpdf for a bit less than a year, and I’ve been involved in the pricing study for quite some time.

Mike Pilawski: I’m the Chief Product Officer. I've been with Smallpdf for the last 18 months. Prior to that, I worked in four other scale-ups, as a COO at Typeform and in similar roles to this one at companies like Leanplum, Vungle, and NativeX.

Júlia Fort: Hi, I'm Júlia and I’m currently leading the UX research team here at Smallpdf. I've been here for about two years.

Smallpdf’s humble beginnings

Mike Pilawski: To give you a little bit of context for the strategy we’re going to outline, let me introduce the company to you and tell you about where we were when we embarked on this journey 18 months ago.

Smallpdf was founded in 2014. We have roughly 130 employees, and our headquarters are in Zurich, Switzerland. We also have growing offices in Barcelona and Belgrade.

Our vision is to build simple yet powerful document solutions for people to do business better and to be the preferred document platform for a million-plus businesses by 2026.

We offer a wide range of tools for editing PDFs and business documents and creating e-signatures. We’ve been used by over a billion users to date, and every month between 55 and 60 million users come to our platform to edit documents. We have 300,000 paying subscribers, and roughly 50% of them are businesses.

I’ll give you a little bit of context for the journey we’ve been on over the last year and a half. In February 2021, Smallpdf was a horizontal solution optimized for SEO, so there was no acquisition strategy and no focus on any specific customer segment. The target was anyone who needed to edit, convert, or organize a PDF or eSign a document.

We had roughly 40 million monthly active users and 250,000 subscribers at that time, including large chunks of customers who would never convert. They’d come back every month and use our tools for free, and they might have been doing that for years with no intention of converting.

We had another group of customers who would sign up for short periods and then churn, usually when their project finished and they didn't need our tools anymore. We also had a very loyal group of customers that had been with us for years.

We wanted to understand what separates those three groups, so we embarked on this journey from building a solution for everyone’s document needs, to a more customer-centric platform built for a specific group of customers that get the most value from us.

We started by identifying and profiling our most valuable customers – Júlia will explain how shortly. Then it took us about six months to leverage those insights, and adjust our acquisition strategy and product accordingly.

With that, we embarked on the final step of the journey, which was to adjust our pricing to fit the needs of our customers and reflect the value they get from our product. Dominik will tell you more about that later.

Identifying the most valuable customers

Júlia Fort: Let me walk you through the first steps towards customer centricity, and tell you how we identified and profiled our most valued customers throughout the whole journey.

We used the ideal customer profile (ICP) framework. The ICP represents the kind of person or organization that brings your business the most value, while also getting the most value from your product or service. For us, that meant narrowing down our large user to a smaller group containing our ICPs.

To make this happen, we defined some success criteria. We started by filtering out all of those customers who were not paying. We were looking for customers who brought our business the most value; therefore, we needed them to be paying.

Later, we defined the metrics that would help us identify the customers who get the most value from our product. For that, we looked at satisfaction and engagement.

To identify the most engaged customers, we focused on both LTV and frequency of use, looking for those customers who were using our product on a weekly or bi-weekly basis.

Quantitative and qualitative profiling

Once we’d identified our most valuable customers, we used quantitative and qualitative analysis to define our ideal customer profile.

We first listed the characteristics that we needed to define those profiles. We wanted to know their demographics, firmographics, buying criteria, reasons to buy, jobs to be done with Smallpdf, needs around these jobs, NPS, and product satisfaction.

So how did we gather all that data? Well, we track a lot of data on our customers, so much of the information we needed was already available. We also identified areas where we were lacking data and did historical data analysis, qualitative interviews, and surveys to fill those gaps.

Let me walk you through these last two. We did a set of roughly 12 interviews with a small group of customers containing our ICPs, where we learned about what made them buy our product, what they were trying to accomplish with Smallpdf, how they learned about Smallpdf, and how they were currently using it.

With all that information from our interviews, we carefully crafted a survey that then was sent out to the larger ICP population.

How to analyze the data

When we’d collected and centralized all the data that we needed, we started on the analysis phase. We brought together a team of experts – UX researchers and data scientists – and looked for patterns among our best customers.

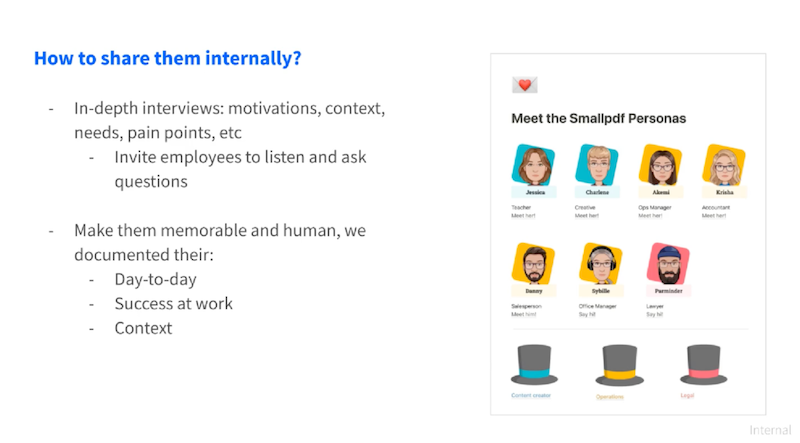

We started grouping these users into different subgroups based on industry, company size, jobs to be done, and behaviors. We tried a lot of different combinations and groupings until we had narrowed it down to seven buyer personas and three hats.

Our buyer personas are mostly defined by firmographics, i.e. industry and department. Our hats are based on psychographic and behavioral patterns. We were looking into what they were trying to accomplish with our product and their ultimate goals when working with Smallpdf.

Let me give you a more concrete example. This is Akimi. She is our accountant buyer persona. At work, she has to wear multiple hats.

She wears the legal hat when she’s signing contracts with vendors, she wears the content creator hat when she creates expense reports, and she wears the operations hat when she deals with documents on a more operational level.

How to share your customer profiles internally

Once we’d defined our profiles and our hats, ran a set of in-depth interviews with our users, inviting all employees to ask as many questions as they wanted and hear firsthand what users wanted to achieve with our product.

We looked into motivations, the context in which they were using our product, needs around the product, and pain points. That helped us add that extra depth of information to our profiles.

Finally, we created some visual cards, which helped us build a storyline behind every one of these personas and hats. In these cards, we wanted to tell a story to make our ICPs more memorable, more human, and therefore more impactful.

Understanding the opportunities and adjusting the strategy

Mike Pilawski: We excitedly brought all these findings to our board, and our board's response was, “You have these customers and that’s great, but are there enough of them to build a sustainable large business?

Is this segment good for us in terms of competitiveness? Can we actually reach them and sell to this segment? Can we build a big enough company to get to an IPO if we focus primarily on this segment?”

Defining our TAM, SAM, and SOM

To answer the board’s questions, we looked at three key metrics:

- Total addressable market (TAM): How much do customers who match our ideal customer profile spend on a service like ours?

- Serviceable available market (SAM): How many customers are reachable for us? Many small and micro businesses are offline, so we might not be able to find them. Plus, since we rely mostly on Google Search, we’re limited by the number of people searching for our services.

- Serviceable obtainable market (SOM): These are customers we can win. These customers prefer products that have the same characteristics as our product – products that are easy to use, bundle a lot of editing tools together, and are online so you don't have to download the client.

We used some traditional research methods that you’re probably familiar with, like top-down analysis and bottom-up analysis, but I want to share one particular hack that I find extremely useful in this situation.

To find out many companies fit the profile you’re looking for, I find that the best source of data is LinkedIn. You can search for a lookalike audience of your customers or, even better, you can test your findings by filtering for the attributes you’ve defined for your ICPs, like company size, industry, job, and location.

Then, to understand how many companies there are, rather than just people who work for those companies, the best hack is to target CEOs. There's usually just one CEO per company, so that will give you a pretty accurate number.

This way, you can quickly understand how many businesses you have to turn into your customers and what kind of market share you need to get to reach your objectives.

Acquisition economics

The second question we had to do to answer was can we grow economically within this segment? The two most important metrics to look at here are how much you're spending to acquire these customers and how much value your company generates from every customer you acquire.

For us, the customer acquisition cost boils down to two simple things. Firstly, there’s the cost of engaging customers in the channel. We don't do much paid advertising, so those costs come from creating SEO-optimized content.

There’s also the cost of hosting a freemium service that our customers can use for free before they decide to convert, versus the conversion rate.

One statistic I can share on this is that our ICPs convert at a rate 70% higher than the rest of our customers, so they’re much more economical for us in terms of customer acquisition.

Then we looked at lifetime value. For us, lifetime value has three components:

- Retention value: How long these customers stay with us. We’re a subscription-based SaaS service, so our income is determined by how many months or years customers pay for the service we provide.

- Expansion value: We only have one plan at the moment, but we’ll soon be adding expansion opportunities, then we’ll start to take this into account.

- Virality value: Our customers use us to share documents with others, collect feedback from their customers, and request signatures on contracts. These are three great ways for them to recommend our product to their partners, colleagues, and customers.

The ICP segment we had identified outperformed every other segment by 30% or more in terms of the metrics above, so from a purely economic perspective, it became very clear that it's a good idea for the company to focus on these particular customers.

Aligning acquisition and product

We’d jumped one hurdle – we had buy-in from the board and the finance department. The next thing was to make sure that we could execute our plan.

Using segmentation data to align acquisition and product

If you want to build a product specifically for a customer group, you first need to know who those customers are.

To find that out, we started with a simple onboarding survey, where we essentially asked our customers three questions and segmented them based on their answers.

This provided us with good visibility into the demographics of our customers as well as which hat they’re wearing or what job they're coming to us to do.

Onboarding surveys are great, but they create some friction, so the next big thing for us is to see whether we can use data activation platforms such as Clearbit or ZoomInfo to eliminate the need to ask customers those questions directly.

The challenge for our service is that we are truly global. While the US is our largest market, we have an enormous number of customers from India, Indonesia, Vietnam, South America, and all across Europe.

Platforms like ZoomInfo and Clearbit tend to be very US-centric with pretty good coverage in other English-speaking markets and some major European markets, so choosing a platform will definitely help with onboarding surveys, but it won’t solve all our problems.

The next thing was to look for behavioral signals and specific keywords from customers that would allow us to better understand what hats they’re wearing and what industries they’re coming from.

Unfortunately, what we found is that our product is used in similar ways across multiple industries and functions, so we can’t understand whether someone's in real estate or education based on their behaviors.

What we can do is look at the tools they’re using to understand which hats they are wearing at any point in time. If someone's wearing a legal hat, they tend to rely on eSign and tools that allow them to organize documents; content creators tend to merge and convert a lot of documents together; people wearing their operations hat tend to do much shorter jobs.

It's not a perfect science, but it allows us to identify what potential sort of hats our users are wearing before even they go through the onboarding process and become our customers.

Aligning acquisition and product processes

Then we had to align our acquisition and product processes, which involves four key steps.

First of all, you need to focus on channels that are dense with ICPs. This was controversial internally because we have channels that generate a lot of visitors to our website, so from a traffic perspective, they're very successful, but the majority of the people who use those channels are not our ICPs. That meant we had to refocus on some new keywords.

The second step is to develop new channels that will help you acquire new customers that fit your ICP. Try to think about these particular customers. What do they do? Where are they? What are they searching for when they need a platform like yours?

A good example of how we’re doing this is by creating templates for contracts and legal documents, so when people are starting their businesses and they need those kinds of templates, they’ll find them on our site, then use our products to turn those templates into actual documents, get them signed, and get their business up and running.

The third step is optimizing product discovery. To do this, you need to run interviews and target the right people for a market study. Right now, we’re doing a large market study of users of similar services to ours, and using our ICP as a guideline for recruitment was critical.

The final step is product validation. If you're doing any usability tests or asking for feedback, you want to make sure you’re asking the right people. Don't just recruit the people who are the easiest to recruit – they might not represent the audience you're hoping to satisfy.

The final tip from what we've learned is that once you know that you have your ICPs (in our case, they constitute roughly 35% of our entire user base) it's a good idea to start tracking metrics separately for them.

If the averages don’t show you the impact you’re hoping to see, you need to dig deeper to understand whether your ICPs are engaging with the things you're building and whether the impact is relevant for them.

Identify pricing that aligns with customer value

Dominik Hiller: Once we’d identified our ICPs and learned what they value, and we’d confirmed that the market is big and attractive enough for us, we started to look at this in the context of a potential pricing change, with the ultimate goal of aligning our pricing to customer value.

Structuring questions

We started with broad structuring questions such as “What problems are we solving for whom?” and “What alternatives, motivations, and frequencies come along with that?” Let me illustrate this with an example.

Let’s say we have a berry store (niche, I know!). We want to know why people are buying those berries. Is Dave trying to live a healthier life and buying berries in an effort to start a new diet? If so, could we provide more value by repackaging our berries as smoothies?

Or is our customer Joelle, the owner of the smoothie bar next door who buys these berries every day to make a living from the people trying to live a healthier life? Joelle doesn't care about the berries being a bit battered, but she wants large quantities and low prices.

Or maybe our customer is grandma Mary, who gets them just once a year to bake her grandson's favorite birthday cake. She's looking for the sweetest, biggest, and prettiest raspberries, and she’s prepared to pay a premium for them.

Dave, Joelle, and Grandma Mary all buy berries, but they all have very different motivations, alternatives, and frequencies for their purchases. Understanding that is key to packaging the right product. This is, to a large extent, what we already know from our ICPs.

Studying price elasticity and analyzing customer data

As well as understanding these motivations, we wanted to sharpen our picture a bit and enrich it with some more quantitative data. To this end, we ran a conjoint study to discover how much our customers and potential buyers value their various product features and how price sensitive they are.

The users participating in the study would see up to 12 different screens showing a range of subscription options, and they had to decide which one they would buy. And this is specific to the conjoint study – they wouldn’t just decide which price they’d prefer but which complete solution would work best for them.

We wanted to know which use cases they were interested in. Would they just want to assemble multiple documents to make them look professional before sending them out?

Or are they more like the Akimi person, who we met earlier, who wears lots of different hats and wants to use every feature? What price would they choose and what combination of platforms do they prefer? Do they want to work on mobile only, or on desktop and mobile?

This conjoint study allowed us to get a good understanding of how users value different features and how price sensitive they are and to connect this more accurately with our types of users and ICPs.

We added some qualifying firmographic questions at the end of the survey, which allowed us to segment participants along with their usage context, persona, industry, company size, and so on.

To run this study, we used a tool called Conjointly. The survey was sent to customers via email in multiple languages. We also added a prompt to our website that would ask users to fill out the survey.

We added more detail to the picture of our customers with an analysis of our actual customer base. That allowed us to observe real-life behaviors, rather than relying entirely on the survey.

We recognized, for example, that some accounts share logins among several people. The good thing about that is that those shared accounts have very high retention rates, so we figured it might be worthwhile creating a package with these account-sharing users in mind.

Armed with a more comprehensive picture of our users and their behaviors and preferences, we were ready to start creating pricing and packaging.

Building proposals

Building our packages, we’re aiming for two matrix goals: we'd like to increase average revenue per user and LTV, and we want to improve customer acquisition.

Our hypothesis is that we’ll achieve the first goal if we manage to align user value more closely with pricing and introduce scalability to the pricing to let our customers start small and then expand with us. We also believe that providing multiple pricing tiers helps improve customer acquisition, so introducing choice should lead to higher conversion rates.

With these hypotheses in mind, we built proposals that combine insights from our various studies and analysis and work particularly well for our ICPs. We now have a mixture of feature-based and usage-based proposals.

The feature-based proposals should provide exactly the right features to the right customers, while the usage-based proposals are oriented around aspects such as storage space and account sharing.

We believe that by fulfilling customer needs with these different proposals, we can increase overall product value, usage intensity, and, in the end, customer retention.

Coming back to our ICPs, meet Charlene. Charlene is a content creator. She currently exclusively wears the content creator hat, meaning she puts together various documents, makes them look nice and professional, compresses them, and sends them off for feedback.

Charlene doesn't need to do eSign or more powerful editing. Eventually, she might, and then she can convert to a different plan where she can wear the operations or legal hat, but for now she's fine with the tier we've put together for all the Charlenes out there. It provides exactly what she needs.

Testing the new pricing and rolling it out

Mike Pilawski: Testing pricing is difficult because it's really hard to go back once you’ve introduced a certain price. You can’t run an A/B test. You can’t have people see a certain price and then see another price a few days later after they clear their cookies.

The approach that we’ve found to be most successful is to choose an isolated market that’s roughly representative of your most important markets.

When I say isolated, I mean it has its own currency and you can limit payments to only that country, using the billing address or the IP address. This market also needs to be big enough to get to statistical significance fast.

For us, since our biggest markets are North America and Europe, the UK is our ideal testing ground. Australia and New Zealand could also work, but we chose the UK for a very simple reason: it’s a big market.

We have quite a lot of customers there, so we know that within a month or two we can learn whether our pricing model works the way we expected or not.

So what do you test? For us, the most important thing is to understand the impact of pricing on conversion. We also want to see which plans people choose.

Within the timeframe of the test, we can't measure LTV, but we can measure 30-day retention as a proxy. We can also measure what percentage of customers churn during the trial or after and indicate that the reason for churning was the price.

Go-to-market

There are several key considerations when you’re rolling out a new pricing model. The first is whether or not to grandfather your existing customers. Should you allow them to keep paying the same price for the platform, or should you take the Netflix route and raise prices for everyone? It depends on your goals.

It’s also worth mentioning an element unique to SaaS, especially in companies like ours where more than 50% of customers are on monthly plans – you can use this as an opportunity for customers to switch to annual plans.

This is a strategy I've used in the past. We offered existing customers the opportunity to move to an annual plan and keep paying the lower price for the coming 12 months. I can tell you from experience that these customers do not move back to a monthly plan afterwards.

The second thing to consider is whether you’re going to move all the customers at the same time or start with specific segments, countries, and features. This allows you to see how customers react to the new pricing and adjust accordingly.

Another option is to roll out the new prices to a smaller sample. If you see that a lot of customers churn as a result, you can reduce that by offering them discounts for a period to smooth them into the new price.

Finally, we can’t forget the importance of communication. No one likes to hear about price increases, but in my experience, there are two good moments to introduce higher prices. One is in a moment like this, where everything is going up, so people are to some extent desensitized. They understand that costs are increasing for companies, so their reaction tends to be less severe.

Better still is to raise the prices when you're releasing a lot of new features. You're providing much more value to your customers and as a result, they’re willing to pay more.

A quick recap

That concludes our journey to customer-centricity and value-optimized pricing. It’s a six-stage process that’s gonna take us two years. It might be possible to do it faster, but changing the company culture and changing how you operate takes time.

Let’s recap the six steps:

1.Identify your loyal customers. Use qualitative and quantitative analysis to understand your ICPs’ firmographics, demographics, psychographics, and jobs to be done.

2. Understand the opportunity (is it big enough? Are you targeting a segment that offers you enough growth?) and adjust your strategy accordingly to focus on those customers.

3. Align your acquisition marketing teams and product teams to those customers and ensure that as they're running discovery, validating products, and running marketing, they’re always clear on who they are trying to reach.

4. Identify pricing that aligns with customer value. This is where you go back to your ICPs and learn how they value the different features and services you offer.

5. Test the pricing. Studies are great, but they’re never 100% accurate. They’re more of a guiding force for you to understand what might work. Never roll out new pricing without testing it first.

Like what you see? Check out our exclusive content with a FoSaaS Membership plan.