Balancing alignment and autonomy

Alignment and autonomy. Ambition and feasibility. Short-term goals and long-term value. As product professionals, we must daily navigate the tensions between these different dichotomies.

When I took on the role as Dashlane’s Product Operations Lead, the first thing I did was interview, observe, and understand what the greatest challenges were in our product development process. Unsurprisingly, a lot of it came down to the complex relationship between achieving alignment and enabling autonomy.

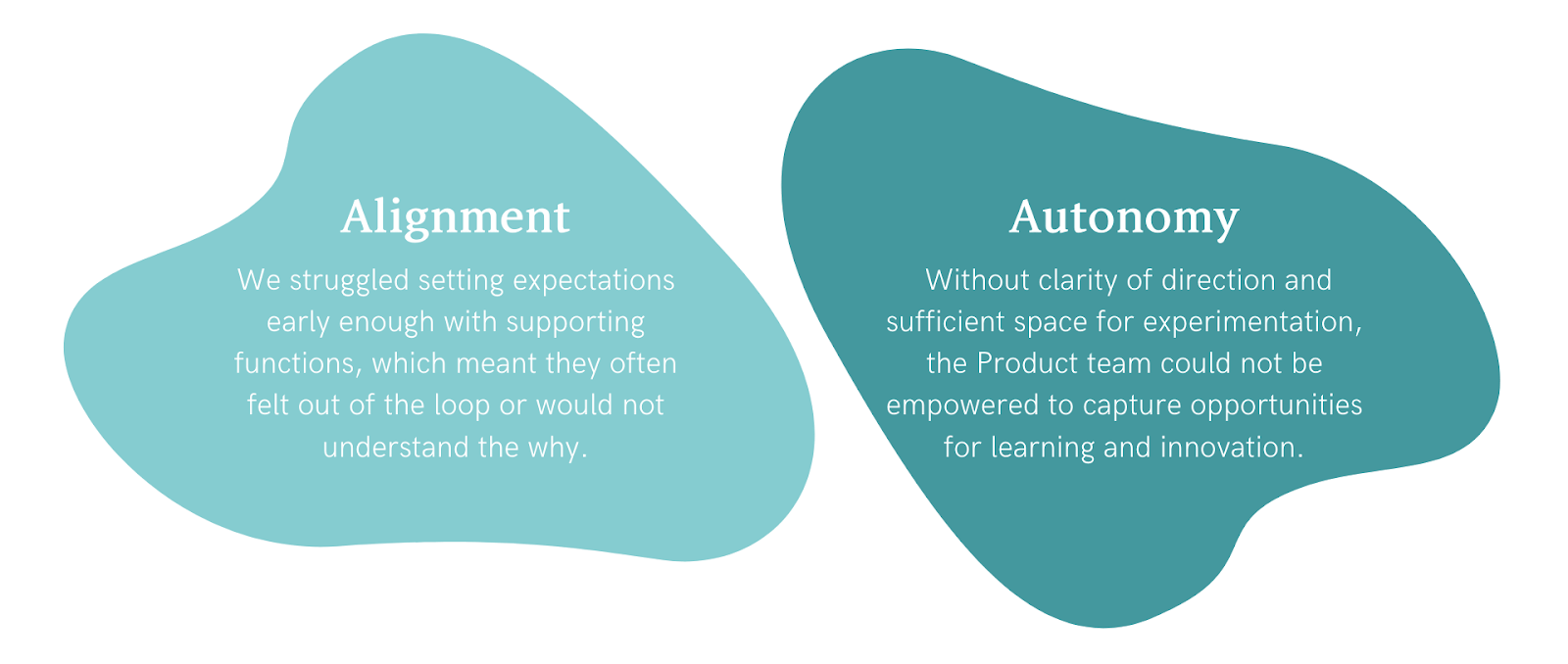

In terms of alignment, we were not always setting expectations early or clearly enough with supporting functions, such as data analytics, product marketing, and customer support. This meant they often felt out of the loop or would potentially contest decisions late in the process given that they did not understand the why behind it.

When it came to autonomy, the team was passionate about the product and excited to innovate on it but were hampered by an unclear vision and limited space for experimentation. Without clarity of direction, the Product team could not be empowered to capture critical opportunities for learning and innovation.

These challenges likely sound familiar, as I have learned from conversations with other Product Operations professionals. They are also exactly the kind of challenges that the Objectives and Key Results (OKR) framework was meant to solve.

A brief history of OKRs

The concept of OKR, now such a ubiquitous term in business, originated already back in the 1950s when management consultant Peter Drucker introduced Management by Objectives (MBO). MBO developed into the OKR framework at Intel in 1968 under the leadership of Andy Grove.

However, OKRs really became popularized thanks to John Doerr, a venture capitalist who learned OKR at Intel and later advised Google to adopt the same framework. Doerr’s 2017 book “Measure What Matters” made his guidance on how to apply the framework accessible to everyone, and now countless tech organizations of all sizes use it.

The essential idea that Doerr communicates in his book is that to achieve great things you need a clearly defined goal, and specific measures used to track the achievement of that goal. More importantly, your goal setting should leave space for failure, and thus learning. This quote particularly spoke to me:

“The OKR framework cultivates the madness, the chemistry contained inside. It gives us an environment for risk, for trust, where failing is not a fireable offense- you know, a safe place to be yourself.”

But are we all applying this framework in the right way to make this possible?

Dashlane has used the OKR framework for years, and we are constantly iterating on our approach to it, which I speak about in more detail with Gerisha Nadaraju on the Product Ops Podcast. OKRs, like any strategic framework, is no silver bullet for organizational excellence. However, when applied correctly, they can be a valuable tool to empower your team to do their best work.

The top three mistakes we make with OKRs

I want to share with you the top three reasons why the OKR framework was failing us, and how we overcame those failures to help us balance alignment and autonomy.

1 - Setting and forgetting OKRs

OKRs are generally reviewed and defined quarterly and can be set at any and all levels of the company. However, this doesn’t mean that they should be set at the start of the quarter, and then not revisited until three months later. Rather, they should serve as a source of motivation and strategic guidance for teams throughout the year.

At Dashlane, we struggled to find the right cadence and forums for revisiting our OKRs more regularly than our quarterly ceremonies. This meant that we often felt rushed in drafting new OKRs before the end of the quarter, and it didn’t become the reflective exercise it was meant to be. This also made it difficult for us to ensure that our OKRs were cascading—that the team OKRs contributed to the product organization’s OKRs and that those, in turn, contributed to the company OKRs—which is important to strengthen accountability.

So how did we solve this?

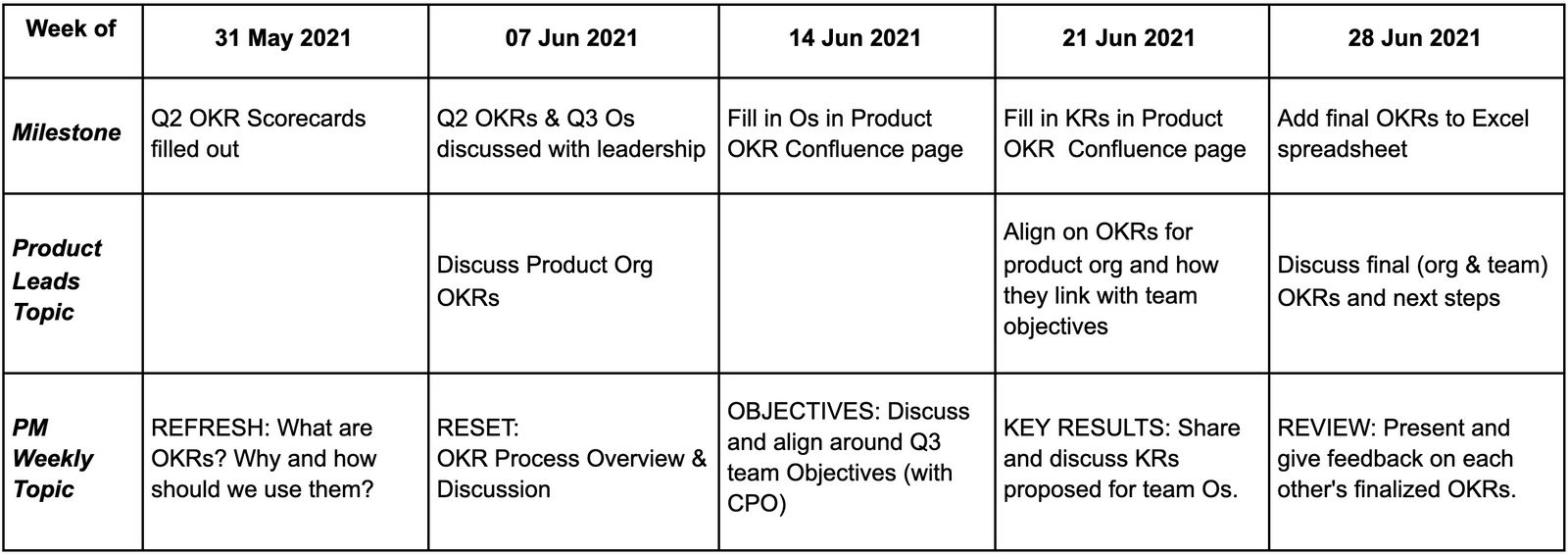

We created an “OKR roadmap", to look at where we could integrate critical discussion and feedback checkpoints on our OKRs throughout the quarter, in existing biweekly ceremonies we had for the Product Management team.

The OKR roadmap also took into consideration how and when OKRs are set at the leadership level and communicated down to teams, to allow them to cascade. After introducing this approach, we arrived at our OKRs two weeks earlier than the previous quarter, and with much more discussion involved, particularly between product managers and product leadership.

Example OKR roadmap:

2 - Setting more initiatives than KRs

It can be difficult to know what to measure as a key result against your objective when objectives can be quite aspirational, inspirational, and ambitious, while key results are meant to be concrete and measurable. For Product Managers, who aren’t as close to the available data as data analysts, it can feel like the data isn’t there to measure – or sometimes it just isn’t and you need to get creative.

In our case, Product Managers were relying a lot on initiatives, which are essentially the things you do to achieve your objective and key result. The distinction between initiatives and KRs can easily get fuzzy, and we needed to break out our definition of them and move more towards the data-driven culture of KRs.

So how did we solve this?

About two months into the last quarter, I initiated an exercise in our weekly Product Management meeting, where we revisited our definition of Objectives, Key Results, and Initiatives. We were able to surface key differences in how we think about and select our KRs and initiatives and establish a more common understanding of each of these components of the framework across product managers and leadership.

For the next quarter, we started to set initiatives aimed at establishing a baseline or setting up the data logs so that for the next quarter we can adopt more KRs instead. This has contributed to stronger relationships between our data and analytics team and our product team.

3 - Setting easy-to-achieve, business-as-usual targets

In our team exercise of revisiting our definition of OKRs, an interesting debate surfaced around how comprehensive the OKR needs to be for a team. Should you go broader in your objective to cover all possible things you might want to do? Can you pursue initiatives that don’t directly impact your KR?

This is where we had the greatest misalignment between product managers and leadership in our interpretation of the framework. PMs worried about being limited by the framework, or set up to fail, and therefore felt demotivated by it. Leadership wanted to see us pursue ambitious objectives, using more aspirational OKRs that Doerr suggests teams should celebrate even at 70% completion.

So how did we solve this?

We began to lean more on leadership to help craft the objectives, to ensure our OKRs were cascading, and to align the scope of the team’s work better with the company strategy. This also helped teams get a better sense of the level of ambition at which to set their goals, and from there it was up to our teams to craft the right KRs and initiatives.

The peer feedback discussions we arranged in our biweekly PM Critique sessions around those KRs helped us shape OKRs that were more aspirational than before, but didn’t feel out of reach for our PMs. It is also worth noting that the OKR framework is divorced from salary and bonus considerations. You should have the license to fail, and thus learn, when applying OKRs to your work. Reminding ourselves of this also bolstered the team’s confidence in using the framework.

Reflecting on what we learned

“We do not learn from experience . . . we learn from reflecting on experience.”

John Doerr, Measure What Matters.

When I reflected on what we have learned so far at Dashlane in our journey with OKRs, the wins are clear. This quarter we reached OKRs that we were confident in and had discussed thoroughly, and we arrived at the finalized set two weeks faster than the quarter before, and in good time before the new quarter began.

This was made possible in part because we created space and time for an open conversation and collective reset around our understanding of the OKR framework, we were clear on our problems to solve and set simple goals to resolve them, and we added structure that greatly simplified and sped up the process.

In addition, we utilized existing ceremonies to save our teams time. For example, we used PM Mastery and Critique sessions to give peer feedback on selected KRs and discuss how objectives across teams laddered up to the product organization OKRs.

There are two final takeaways from this experience I’d like you to consider after reading this. First of all, the OKR framework is a useful tool, but to successfully apply it, note the root problems for why your company struggles with the tension between alignment and autonomy.

Secondly, OKRs are only one piece of the puzzle - consider the process and cadence around whatever framework you are using for goal-setting, and create the space for discussion both vertically and horizontally. This will allow you to truly reflect on your experience, and harness the power of OKRs for inspiring your team to raise the bar.